How to Stay Calm When Your Child Hurts Your Feelings

I’d like to share with you the story of how this post came to be, and what inspired my reflection on what to do when your child hurts your feelings.

It all started very normally: me walking with my 14-year-old daughter to her school bus. It’s a 15-minute walk, and whenever I can, I like to tag along. It gives us a little time to chat — just the two of us, without her brothers around.

That morning, she opened up about her pimples and how annoying they were. We chatted over some potential solutions, but it turned out that washing her face felt even more annoying — because, as she dramatically demonstrated, it made her hair wet.

I misinterpreted her performance as playful acting and laughed.

She stopped dead in her tracks.

Through gritted teeth, she asked why I was even there — and told me to go home.

In a second, I realised I had hurt her feelings. I tried to explain, but she wasn’t having any of it. She marched ahead, leaving me ten meters behind, nursing a cocktail of hurt, guilt, and discouragement.

But I have a rule: Never stay more than 90 seconds in a negative emotion. So I shook myself out of it and just kept walking.

As my daughter worked through her feelings too, she gradually slowed down — tying a shoelace here, checking her phone there — until I caught up.

At the bus station, she said she was sorry. I said I was sorry too — for hurting her feelings.

On the walk home, I kept reflecting.

How quickly things escalated. How often small moments turn into bigger hurts. How often I hurt my children without meaning to — and how often I let myself be hurt too.

It reminded me of the Second Toltec Agreement: Don’t take anything personally.

But how do you actually do that?

And why does it hurt so much in the first place?

These days, if you look anywhere — from social media to movies to parenting books — you’ll see it:

Today’s parents are expected to be more emotionally intelligent, more available, more aware than any generation before us.

That’s a beautiful evolution. But it also comes with a heavy responsibility.

When something like the incident with my daughter happens — when you accidentally hurt your child’s feelings — it’s easy to feel like a complete failure. Like you’re not doing it right.

But that’s not the whole story.

First, because if you’re reading this post, it shows you care — and caring is the first and biggest step.

Second, because our children don’t need to live in a bubble where no one ever hurts their feelings.

They need to learn how to navigate hurt. To manage pain, disappointment, and emotional bumps with wisdom and resilience.

Think of it this way: you wouldn’t keep your child strapped into a baby seat on your bicycle until they’re eighteen. You teach them to balance, to brake, to fall — and to get back up again, so they can ride their own bike.

Emotional resilience works the same way. And you are their main role model to learn it.

In this post, I’ll walk you through the reflections and research I did about emotional hurt after the incident with my daughter and practical ways to move through hurt without breaking the connection.

1. The Invisible Sting: Why Does It Hurt So Much?

This is the first question that came to my mind: Why did my daughter’s words hurt me? They are just words. And yet, everyone who’s ever been heart broken knows that emotional pain is real.

Research shows that we are not crazy. When someone says something cruel, our brain activates the anterior cingulate cortex—the same region involved when we hurt ourselves physically.

This is because humans evolved as social creatures; being accepted by the group was once key to survival. So rejection, judgment, or shame hits us hard—it feels dangerous, even if we know it isn’t physically threatening. Of course, you might argue that we are not hunter-gatherers anymore, but think about it: if human history were compressed into 24 hours, we lived as hunter-gatherers for 23 hours and 50 minutes.

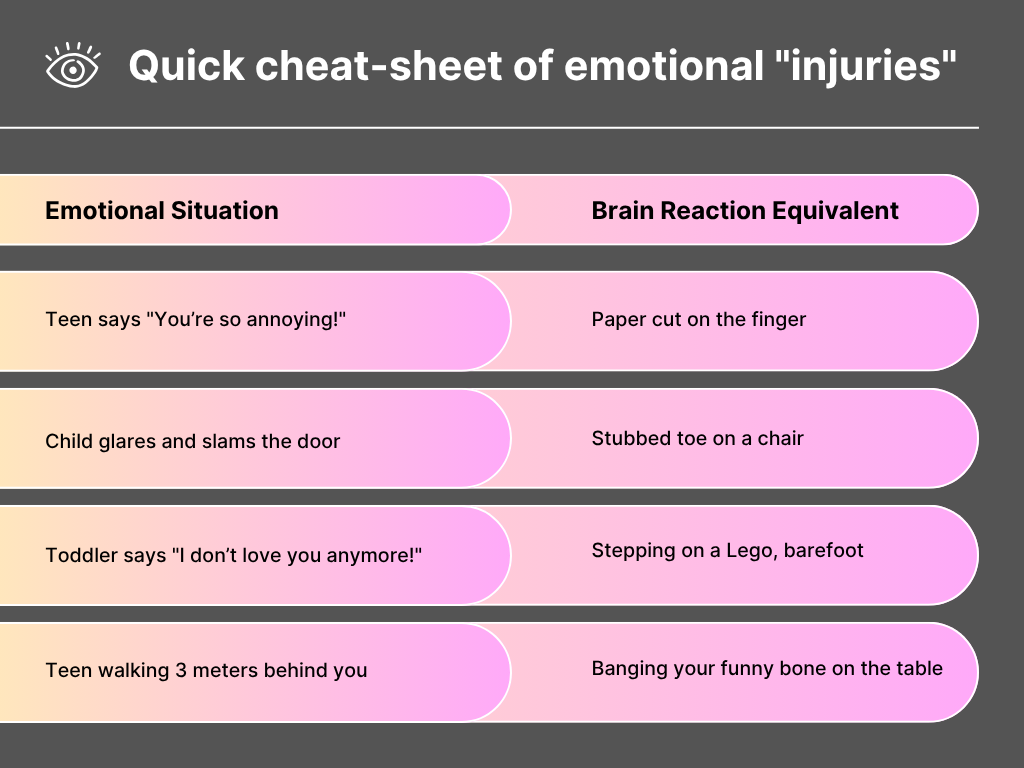

I thought about this and created this little list for future use:

Though we can all agree on the fact that emotional pain does hurt, you might wonder: why does the same comment hurt one person deeply and does not affect another at all?

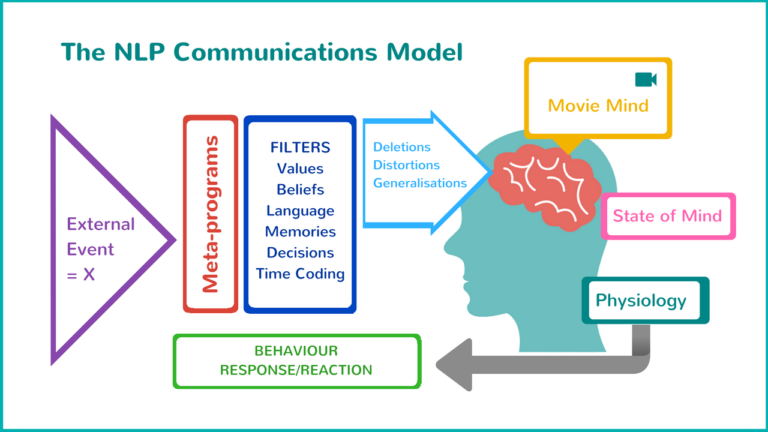

It’s all about perception and meaning.

Your brain doesn’t just hear words — it interprets them through layers of past experiences, beliefs, and emotional history. You actually find these layers on several levels: perception, interpretation, reaction — so plenty of room for bias.

For example, if you once had a parent who constantly teased you, a harmless joke might hit a hidden bruise. But someone else without that wound? They shrug it off, like water off a duck’s back.

It’s not what’s said to you. It’s what it means to you

And often, you don’t even consciously realise why it hurt until much later (if ever). But we’ll come back to that.

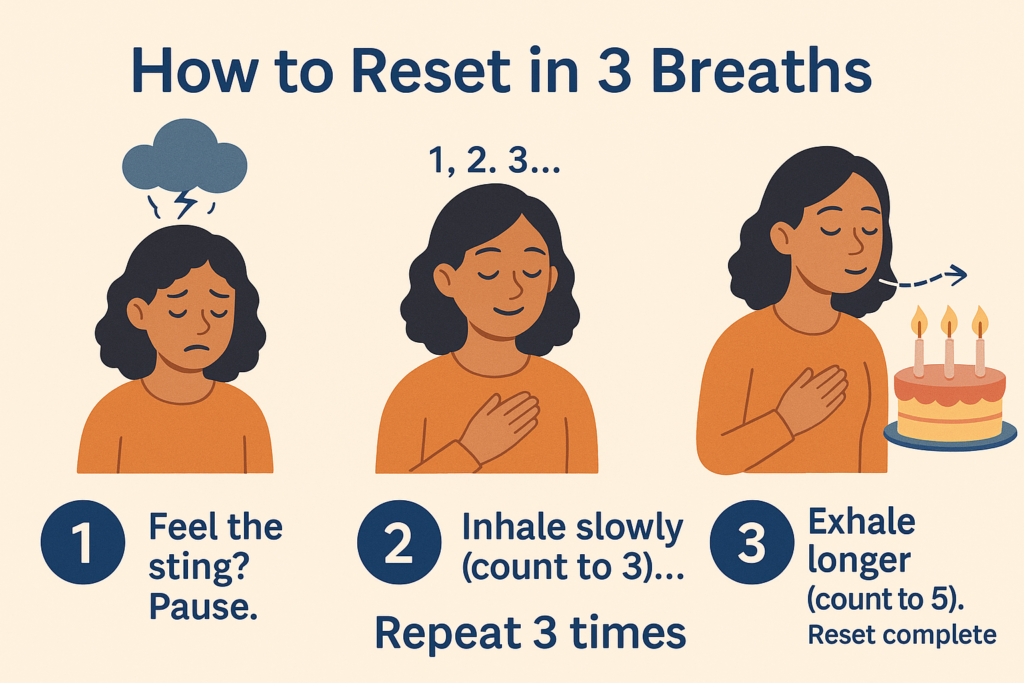

Practical Tip:

When you feel that sting, pause and take three slow breaths — making sure your exhale is longer than your inhale, as if you were gently blowing out birthday candles.

This simple shift signals your nervous system that you are safe, even if your emotions feel intense. It defuses the hunter-gatherer programming.

It may not erase the discomfort completely, but it will soften the reaction and help you stay connected to yourself — and to your child.

Let’s look at the simplest of example: even though I must have said it a million times to my mum as a child myself, I couldn’t help feeling stung when my son tried my three-hour-labour vegan cheese and zucchini and said: “That’s not good.”

I know he didn’t mean to hurt me. I know he’s only eleven, and maybe — just maybe — it’s time he remembers to say “I don’t like it” instead of “that’s not good “.

And yet, it stung. Why?

Because emotions aren’t logical — they’re fast and automatic. Which brings us to the next layer of our quest.

2. The Waves Beneath: Why We React So Strongly.

Let me repeat myself: here’s the slightly inconvenient truth about emotions: they aren’t logical. They are fast, automatic, and sometimes — completely irrational.

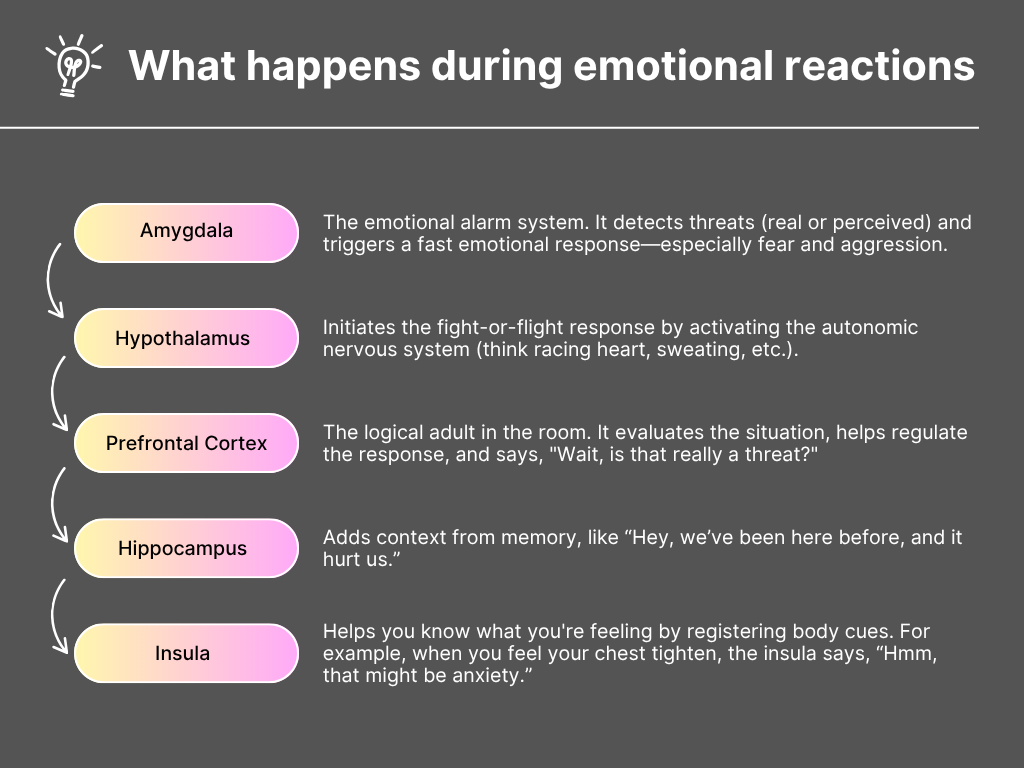

This is not a personal flaw. It’s how your brain is wired. When something emotionally charged happens — like your child rolling their eyes or rejecting your lovingly cooked vegan cheese — the first part of your brain to react is the amygdala. That’s the little almond-shaped structure whose job is to detect threats and send up the alarm.

Now here’s the kicker: the amygdala reacts before your thinking brain — the prefrontal cortex — has even finished tying its shoelaces. So your body is already tense, your tone is sharper, your heart is racing… before you’ve consciously decided to do anything at all.

To understand what’s going on inside your head (and body) during these moments, here’s a quick look at the main players involved:

See, in the heat of the moment, so much happens, but usually we only understand it later, when one calms down. The other day, my teenager told me, “Mum, you’re always so dramatic.”She wasn’t shouting. She wasn’t even upset. She was just… stating it. Calmly. Casually. As if describing the weather.

Still, something in me tightened.

Before I knew it, I heard myself replying, “Well, maybe if I didn’t care so much, I wouldn’t seem so dramatic.”

Not exactly my most mature moment.

Later, as I replayed the conversation, I realised it wasn’t really her words that upset me — it was what they touched. That deeper part of me that is trying so hard, always — and feels she’s only seen when she goes overboard.

In that moment, my daughter hadn’t meant to hurt me.But the reaction came anyway, stirred by old emotions I didn’t even know were waiting there.

Why Does This Happen? These are called emotional triggers — past hurts that live quietly under the surface until something scratches them.

And because emotions act faster than thought, your body can react before your mind even knows why.

The good news? Once you notice it happening, you can shift out of automatic reaction and back into conscious response.

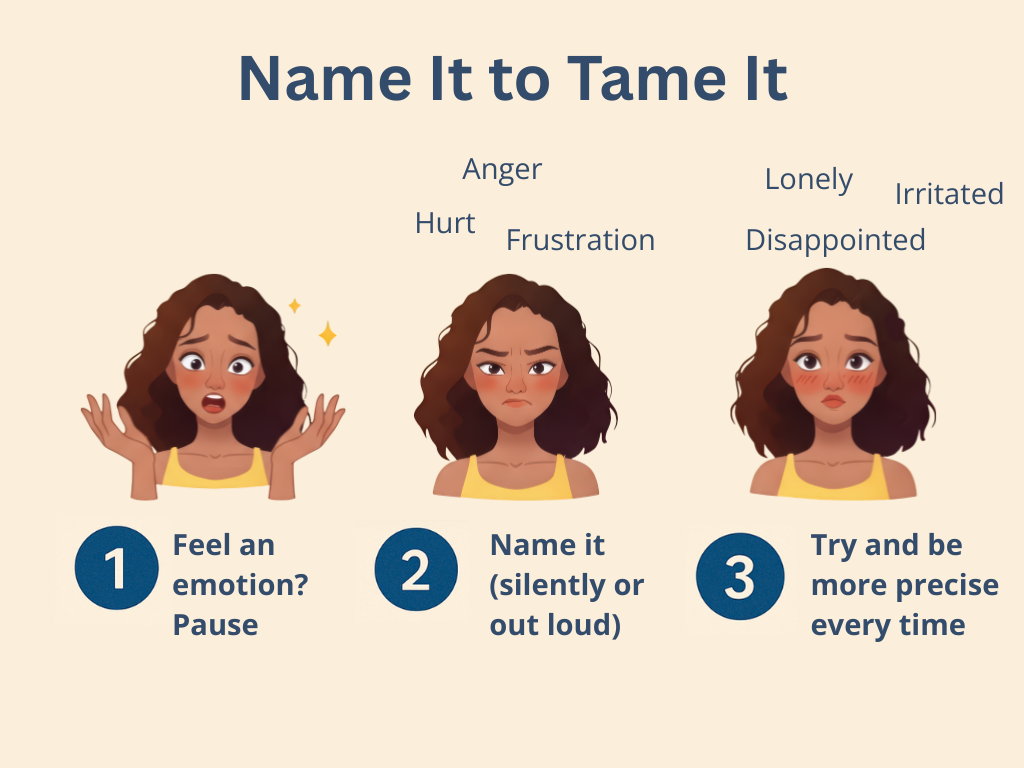

Practical Tip: “Name It to Tame It”

Let me show you a simple yet powerful strategy.

When you feel a strong emotion surging up, pause and literally name it — silently or out loud.

“This is hurt.” – “This is anger.” – “This is sadness.”

This may sound simple, but it’s powerful. Labelling an emotion activates the more logical, reflective parts of your brain, which in turn helps calm the more reactive emotional centres.

The feeling won’t disappear instantly, but you’ll feel more grounded, more in control.

And the more precise your label, the more effective the calming effect. This is called emotional granularity — the ability to name what you feel with nuance.

👉 Not just “bad,” but “overwhelmed,” “lonely,” or “discouraged.”

👉 Not just “angry,” but “irritated,” “resentful,” or “disappointed.”

The better we get at naming our feelings, the better we get at managing them.

But our reactions to what is said doesn’t stop at our emotions and past wounds, there is another actor that comes in the mix: our attachment system.

3. The Deeper Roots — Our Attachment System

Our nervous system is built for connection. Remember what we said back in Chapter 1 about those hunter-gatherer ancestors? Being part of a group was essential for survival, and disconnection could mean danger. That wiring didn’t disappear when we invented indoor plumbing or smartphones.

It’s still very much with us.

From the moment we’re born, we seek closeness, comfort, and safety in the presence of another. That bond, especially with a caregiver, is what the psychologist John Bowlby called attachment. It’s how we learn whether the world is safe, whether our needs will be met, and whether our emotions will be understood.

When those early bonds are consistent and nurturing, we develop what’s called secure attachment. This doesn’t mean a perfect childhood — it means we learned, over time, that we matter, and that closeness is safe.

And while attachment begins in childhood, it continues to evolve throughout our lives, shaped by our experiences, relationships, and especially how we repair after conflict.

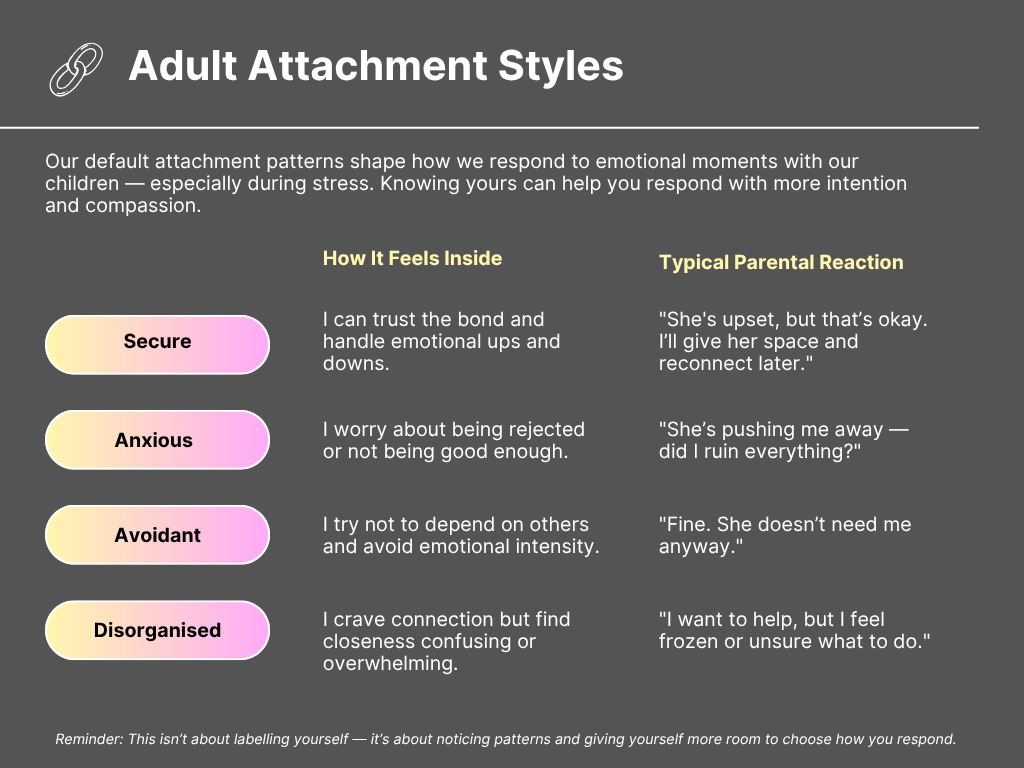

Psychologists describe several adult attachment styles that shape how we respond in close relationships, especially under stress.

– Secure: You trust the bond and can navigate emotional ups and downs with confidence.

– Anxious: You often worry about rejection and may become overly sensitive to signs of distance.

– Avoidant: You tend to downplay your own needs and retreat from emotional intensity.

– Disorganised: You crave connection but may also feel overwhelmed or confused by it.

This is why our children’s reactions can feel so personal. Their withdrawal, anger, or rejection touches that deep part of us wired to stay connected at all costs. And that’s also why our own reactions in those moments can be so intense.

These patterns aren’t fixed labels — they’re learned strategies, usually formed early in life. And here’s the good news: awareness gives you choice.

Scroll down to the graphic below and see which style you recognise most in yourself. Not for judgment. For clarity. Because the more you understand your own blueprint, the easier it becomes to respond, rather than react, in moments of emotional heat.

Let me illustrate this for you:

I grew up very people-pleasing — a natural result of Swiss education, with its polite restraint and strict cultural etiquette. Emotions were kept tidy. You didn’t make waves. You helped when asked.

So I remember clearly my first “no.” I must have been about thirteen when my mum asked me to go to the neighbour’s to borrow some milk. I hated doing that — I hated ringing people’s doorbells and asking for things.

So, newly promoted to teenager, I said “no.”

My mother was so shocked, she told that story to everyone for weeks: “She used to be so sweet, so helpful — and now, suddenly she says no?!” You would think I had broken a sacred contract.

I could feel she believed something fundamental had been lost and she didn’t know how to fix it. But the truth is: there was nothing to fix. I still loved her, I still respected her, I still wanted to help her. I just didn’t want to knock on someone’s door and ask for milk. My mother, who leaned more toward the anxious side, tried harder after that to reassure herself we were close — constantly asking, checking, fussing — and I, overwhelmed by it all, began pulling away. I became more avoidant with her, not because I didn’t love her, but because I felt smothered by the fear behind her love.

Because this is what happens when different attachment styles collide. It becomes harder to meet each other. We miss the intention behind the words. We take things personally. And everyone ends up feeling a little more alone.

This isn’t about blaming yourself — as I’ve made abundantly clear, most of this happens in your subconscious. It’s about realising that awareness is freedom.

Your attachment style was shaped from a very young age, and often through pain you never chose. But now that you see it, you get to choose how you respond. And when you respond differently, you change the dance between you and your child.

Here are a few steps you can take if you want to work on your attachment responses.

Step 1: Learn to Pause the Reaction

Your nervous system gets hijacked in conflict. The part of you that feels rejected, dismissed, or not enough—it’s not reacting to your teenager… it’s reacting to something much older.

Breathe. Ground. If needed, walk away for a few minutes. Train yourself to come back to your child as the adult version of yourself—not the wounded inner child.

Use this question in the heat of the moment: “Is this about them, or about something in me that hasn’t healed yet?”

Step 2: Begin to Self-Regulate Instead of Seeking Regulation Through Others.

If you want to be a safe emotional container for your teen, you must first become that for yourself. You can ask:

What do I need that I don’t get? or what did I need that I didn’t get (as a child, a teenager, a younger version of myself)

How can I give that to myself now?

By doing that, you model self-regulation, emotional literacy, and unconditional love to your family.

Step 3: Create a “secure self” vision.

Imagine: “If I were securely attached, how would I act in this moment?”Then take one small step in that direction. This gently rewires patterns by acting as if you’re already secure.

Beyond the Hurt: A Spiritual and Philosophical Path to Wholeness

Why do some words from our children leave such a deep mark? Why do we sometimes return, over and over, to the same emotional wound, despite all the awareness, all the breathing, all the strategies?

Because healing isn’t just emotional. It’s also spiritual.

This chapter is about stepping beyond strategies — into a deeper kind of knowing. One that sees hurt not just as something to fix, but something that can elevate us. I invite you to discover how some different teachings can bring a new light to our quest.

“What stands in the way becomes the way.” — Marcus Aurelius

The stoics, for example, believed that adversity is not the enemy. It’s the path.

The Stoics believed that every difficulty life offers is also an invitation to grow in virtue. Courage. Patience. Wisdom. Self-restraint. Emotional wounds, in this view, are not obstacles to parenting well — they are the very material from which good parenting is made.

So instead of asking, “Why did this happen to me?” I’ve started asking, “What quality is this moment asking me to develop?”

It won’t make the pain vanish. But it will give it purpose.

Because the moment becomes less about being hurt, and more about becoming whole.

“When another person makes you suffer, it is because he suffers deeply within himself.” — Thích Nhất Hạnh

Buddhism teaches that suffering comes from attachment to the self-image — to being seen a certain way, valued a certain way. When our children “hurt” us, it’s often our ego reacting, not our true self.

Suffering often begins when we cling to identity: the “good mother,” the “sensitive daughter,” the “misunderstood parent.” You can ask yourself: Who is the “me” that feels wounded?

And to bring back calm and compassion, you can use the mantra « Om Mani Padme Hum », which is one of the most revered mantras in Tibetan Buddhism.

“Nothing others do is because of you.” — Don Miguel Ruiz

Your child rolls their eyes or pushes you away, it feels personal. But it rarely is.

Their reaction is a reflection of their inner world, not a judgment of your worth. Just like your reaction to their words is a reflection of you.

When we take things personally, we make someone else’s moment our identity. When we don’t, we create space for grace. Space to see our child not as an opponent, but as another human learning how to be.

There is a crack in everything — that’s how the light gets in.” — Leonard Cohen

All spiritual traditions acknowledge that life is not about avoiding pain, but being transformed by it. Can you trust that even in hurt, love is still present? Can you believe that grace can come through the mess?

Your child does not need a perfect parent. They need a present one. One who can say “I’m sorry.” One who believes that love doesn’t disappear when things get messy — in fact, that’s often when it shows up most clearly.

Practical Tip: Learn to Find the Good

The next time you go to bed, ask yourself: “Where did love show up today?”.

Let the answer come — a smile, a pause, a kind word, a moment of restraint. Even if the day felt messy, there will be something. Let that be the final imprint on your heart before sleep.

Closing Reflection: You Are Enough

I bet you can think of a moment when your child said something that stung. Maybe they rolled their eyes, or they told you you were “so annoying.” They might have muttered something under their breath, or stormed off with the drama of a Shakespearean actor.

And you felt it — that sting. Vexed, hurt, cross. Maybe even muttering a few things yourself afterwards.

But now — now you know better.

You know that sting isn’t proof you’re failing as a parent. It’s just your brain, still wired like a hunter-gatherer, trying to stop you from being kicked out of the tribe. You know emotional reactions are fast, messy, and often based on things that happened long before your child ever learned to talk back. And you know that your child’s words are theirs — not a definition of your worth.

You’ve seen how attachment styles, past wounds, and emotional echoes can turn the best intentions into meltdowns (on both sides).

But you’ve also seen that awareness opens the door to change.

You’ve learned how to pause. How to reconnect. How to stop dragging around emotional pain that was never meant to be carried so far.

And as Boris Cyrulnik so perfectly put it:

“Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.”

So, drop the guilt and keep the love, because now you know what to do when your child hurts your feelings.

And remember: you are not a saint. You are a mother. Which is infinitely messier — and infinitely more powerful.

Now go make a cup of tea, text a friend this post, and give yourself a bit of credit.

You’ve earned it.

✨

Thank you for reading, I hope you found this inspiring and that you are ready to try a couple of ideas straight away! Please feel free to share this post with other mothers who may benefit from this information.

Don’t Forget To Join Our Community To Get Inspiration And Tips Straight in Your Mailbox

I wish you all the best with your kids. Always remember — we’re all doing the best we can in any given moment, so try not to judge yourself too harshly. Be confident and listen to your intuition. If what you do comes from a place of love, then you’re already on the right path.

If this post resonated with you — if you’ve ever walked ten paces behind your child, wondering if you’re ruining everything — come join us on Instagram.

It’s where I share reminders, reflections, and the odd parenting confession… for mums figuring it out one heart-twinge at a time.

References:

Image filters: https://www.cexperiences.com/how-to-move-up-the-emotional-scale/the_nlp_communications_model/

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290-292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089134

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Basic Books.

Ruiz, Miguel. (2001). The Four Agreements: A Practical Guide to Personal Freedom. Amber-Allen Publishing.

https://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/index.php?title=Om_Mani_Padme_Hum

If you want more resources, ⬇️ keep scrolling ⬇️

Looking for a way to set boundaries that feel fair for everyone? Here’s your home guide to healthy boundaries.

If your child is or is becoming a teenager, check out our parenting guide for teenagers!

Discover other articles you might like